Homeless Being Incarcerated Over and Over Again

Home Folio > Reports > Nowhere to Go: Homelessness amongst formerly incarcerated people

Nowhere to Go: Homelessness amid formerly incarcerated people

By Lucius Couloute Tweet this

August 2018

It's hard to imagine edifice a successful life without a place to telephone call home, simply this bones necessity is oft out of accomplish for formerly incarcerated people. Barriers to employment, combined with explicit bigotry, take created a niggling-discussed housing crisis.

In this report, we provide the get-go guess of homelessness amid the 5 million formerly incarcerated people living in the United States, finding that formerly incarcerated people are most x times more than likely to exist homeless than the full general public. We break down this data past race, gender, age and other demographics; we also show how many formerly incarcerated people are forced to live in places like hotels or motels,⤵ just ane pace from homelessness itself.

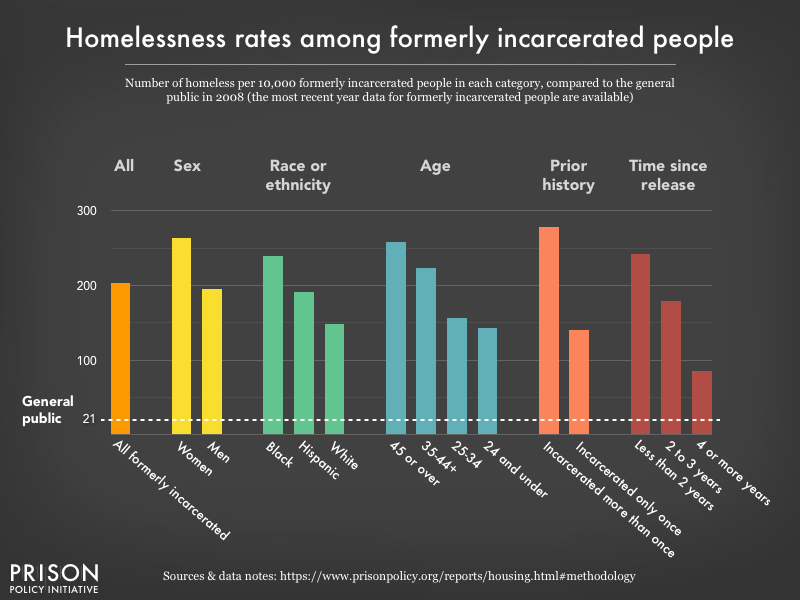

Figure 1. 2% of formerly incarcerated people were homeless in 2008 (the most recent year for which information are available), a rate nearly x times higher than amidst the full general public.

Figure 1. 2% of formerly incarcerated people were homeless in 2008 (the most recent year for which information are available), a rate nearly x times higher than amidst the full general public.

Homelessness among formerly incarcerated people

The transition from prison to the community is rife with challenges. But before formerly incarcerated people tin address health problems, find stable jobs, or learn new skills, they need a place to alive.

This study provides the first national snapshot of homelessness amid formerly incarcerated people, using data from a little-known Bureau of Justice Statistics survey. Our analysis builds on existing research showing that by incarceration and homelessness are linked. National research suggests that up to 15% of incarcerated people experience homelessness in the twelvemonth before admission to prison house.1 And urban center- and land-level studies of homeless shelters find that many formerly incarcerated people rely on shelters, both immediately after their release and over the long term.2

Nosotros observe that rates of homelessness are especially high amongst specific demographics:

- People who have been incarcerated more than than once⤵

- People recently released from prison⤵

- People of colour and women⤵

In the following sections, we take a closer look at these populations. We also interruption down how many formerly incarcerated people are living in marginal housing⤵ - a step abroad from homelessness.

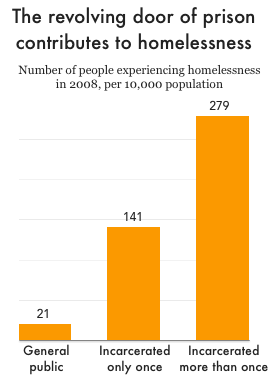

The revolving door & homelessness

We find that people experiencing cycles of incarceration and release - otherwise known as the "revolving door" of incarceration - are too more likely to be homeless.iii

People who have been to prison but once experience homelessness at a rate nearly seven times higher than the general public. Merely people who accept been incarcerated more once have rates 13 times college than the general public. In other words, people who have been incarcerated multiple times are twice as likely to be homeless every bit those who are returning from their first prison house term.

Unfortunately, being homeless makes formerly incarcerated people more likely to exist arrested and incarcerated again, cheers to policies that criminalize homelessness.4 As law enforcement agencies aggressively enforce "offenses" such as sleeping in public spaces, panhandling, and public urination - not to mention other depression-level offenses that are more than visible when committed in public - formerly incarcerated people are unnecessarily funneled back through the "revolving door."

Homelessness amid recently-released individuals

Previous enquiry has shown that formerly incarcerated people are about probable to be homeless in the menstruum soon afterwards their release.v Our information supports this research: We find that people who spent two years or less in the community were more than twice as probable to be homeless every bit those who had been out of prison house for four years or longer.

Homelessness among recently released individuals is a fixable problem. States tin can - and should - develop more efficient interagency systems to help formerly incarcerated people observe homes. But longer-term support is too needed: Our assay found that even people who had spent several years in the community were iv times more likely to be homeless than the full general public.

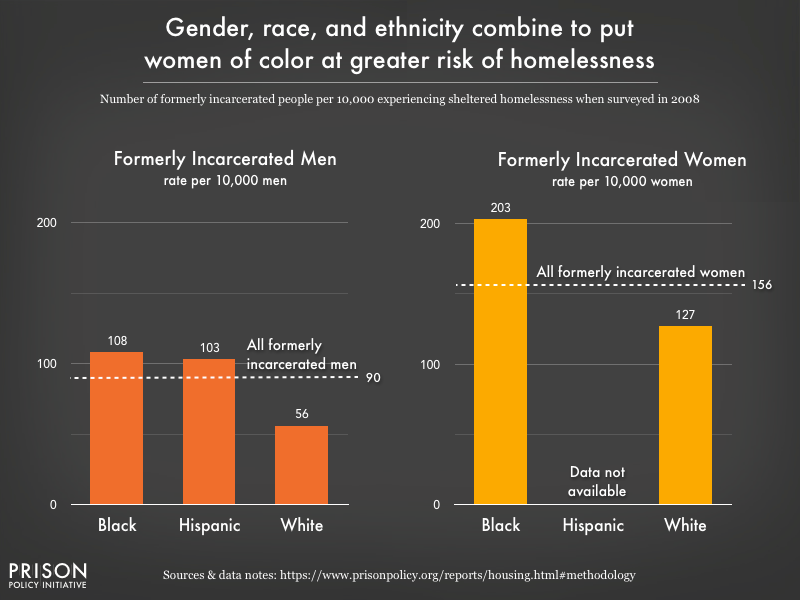

A closer look: sheltered and unsheltered homelessness past race and gender

Within the broad category of homelessness, there are two distinct populations: people who are sheltered (in a homeless shelter) and those who are unsheltered (without a fixed residence).

We find - in keeping with previous research on homelessness in the full general public - that the sheltered and unsheltered formerly incarcerated populations have significant demographic differences.half dozen

For example, nosotros discover of import differences by gender. Overall, formerly incarcerated women are more likely to exist homeless than formerly incarcerated men. Merely among homeless formerly incarcerated people, men are less likely to be sheltered than women, whether for reasons of availability or personal choice.

| Homeless(Charge per unit per 10,000) | Sheltered(Rate per 10,000) | Unsheltered(Rate per 10,000) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 195 | 90 | 105 |

| Women | 264 | 156 | 108 |

| Full | 203 | 98 | 105 |

Unsheltered homelessness by race and gender

We discover that formerly incarcerated Black men take much higher rates of unsheltered homelessness than white or Hispanic men.

The information also suggests that women of color feel unsheltered homelessness at higher rates than white women. (Though there were too few unsheltered formerly incarcerated Blackness and Hispanic women in our dataset to clarify,7 the rate of unsheltered homelessness amongst white women was substantially lower than the rate for women generally. Therefore, it is articulate that formerly incarcerated Black and/or Hispanic women experience unsheltered homelessness at significantly higher rates than white women.)

| Black(Rate per 10,000) | Hispanic(Rate per 10,000) | White(Rate per 10,000) | Total(Rate per 10,000) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 124 | 82 | 81 | 105 |

| Women | due north/a | northward/a | 87 | 108 |

| All | 123 | 90 | 82 | 105 |

Sheltered homelessness by race and gender

Black women experienced the highest rate of sheltered homelessness - nearly four times the rate of white men, and twice as high as the rate of Blackness men. Combined with our breakdowns of race and gender separately (encounter Figure 1), this analysis shows that Blackness women face severe barriers to housing after release.

Figure 2. Rates of sheltered homelessness amid formerly incarcerated people differ widely by race and gender, with Black women nearly iv times more likely than white men to be living in a homeless shelter.

Figure 2. Rates of sheltered homelessness amid formerly incarcerated people differ widely by race and gender, with Black women nearly iv times more likely than white men to be living in a homeless shelter.

The high rates of homelessness among Black women are peculiarly hitting in lite of our like finding, last month, that unemployment rates among formerly incarcerated Black women were higher than any other demographic group.8 Our findings illustrate that Black women, in particular, take been excluded from the social resources necessary to succeed after incarceration.

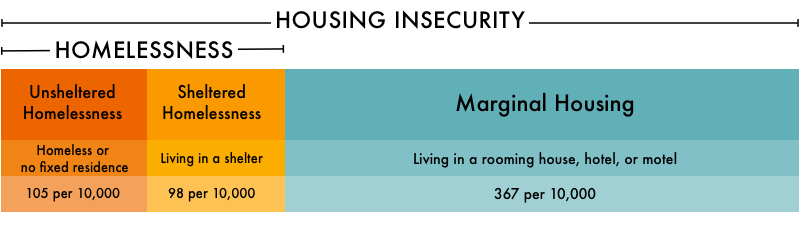

Almost homeless: Housing insecurity among formerly incarcerated people

Measuring homelessness amid formerly incarcerated people is a critical step forward, but it doesn't fully capture the exclusion of formerly incarcerated people from stable housing - the kind of housing near people need to thrive and contribute to their communities.

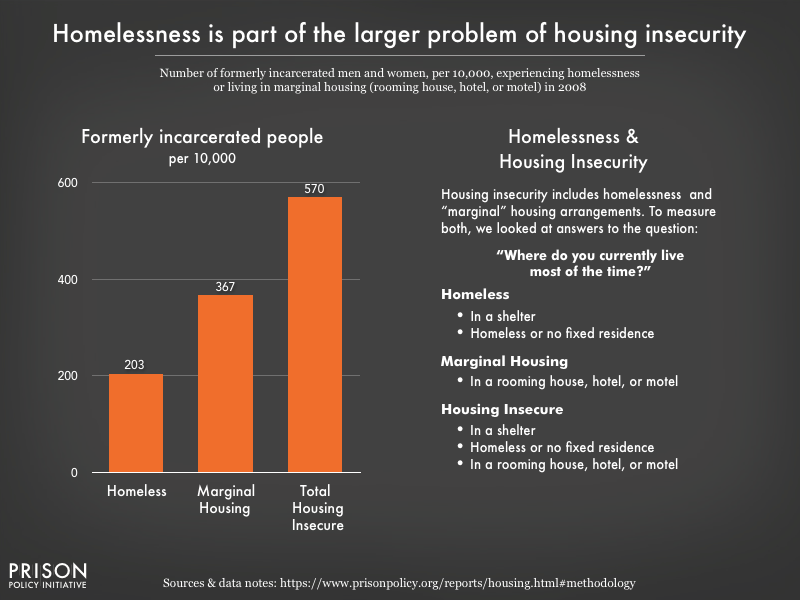

To better measure the scope of the problem, we created a 2nd metric - housing insecurity - that includes formerly incarcerated people who are homeless (both sheltered and unsheltered) besides as those living in marginal housing like rooming houses, hotels, or motels.9

Figure 3. Housing insecurity includes people who are homeless likewise as those living in marginal housing. 570 out of every 10,000 formerly incarcerated people fall into i of these categories, making housing insecurity most 3 times more common than homelessness alone.

Figure 3. Housing insecurity includes people who are homeless likewise as those living in marginal housing. 570 out of every 10,000 formerly incarcerated people fall into i of these categories, making housing insecurity most 3 times more common than homelessness alone.

Housing insecurity provides a more than realistic measurement of the number of formerly incarcerated people denied access to permanent housing. While we found that 203 out of every 10,000 formerly incarcerated people were homeless, almost three times as many - 570 out of every 10,000 - were housing insecure.

Nosotros also uncovered notable demographic differences by expanding our view to the housing insecure population: Hispanics, for example, were more likely than people of any other race to alive in marginal housing. Men had much higher rates of marginal housing than women, resulting in high rates of housing insecurity. And older formerly incarcerated people experienced the highest rates of housing insecurity.

Ideally, this written report would direct compare the prevalence of housing insecurity amongst formerly incarcerated people to that of the general public. Unfortunately, the equivalent national statistics on housing insecurity do not notwithstanding exist. Fifty-fifty without that comparison, nonetheless, it's clear that having been to prison is a major gamble factor for housing insecurity.

Causes and consequences of housing insecurity after release

Stable housing is the foundation of successful reentry from prison. Unfortunately, as our information show, many formerly incarcerated people struggle to notice stable places to live. Discrimination by public housing regime and private property owners,10 combined with affordable housing shortages,11 continues to drive the exclusion of formerly incarcerated people from the housing market.

Part of the problem is that belongings owners and public housing authorities have the ability to implement their own screening criteria to decide if an applicant merits housing12 - a procedure that oftentimes relies upon criminal tape checks as the chief source of information. In do, this means local authorities and landlords have broad discretion to punish people with criminal records fifty-fifty after their sentences are over.

The utilize of credit checks, exorbitant security deposits, and other housing application requirements - such as professional references - tin can besides human action as systemic barriers for people who have spent extended periods of time away from the community and out of the labor market.13

Excluding formerly incarcerated people from safe and stable housing has devastating side furnishings: It tin reduce access to healthcare services (including addiction and mental health handling),xiv make information technology harder to secure a chore,15 and forestall formerly incarcerated people from accessing educational programs.sixteen Severe homelessness and housing insecurity destabilizes the entire reentry process.

Fortunately, on-the-basis advocates across the country have fabricated important progress in reducing overall homelessness.17 But an estimated 550,000 people are however homeless on any given night in the United states,18 many of them individuals with a history of criminal justice arrangement contact. Information technology's critical that policymakers develop comprehensive responses to this problem, rather than continuing to punish those without homes.

All people - and particularly those carrying the stigma of criminalization - need these solutions. In such a wealthy country, it'southward fourth dimension nosotros eliminate homelessness for good.

Determination

This study provides the get-go national estimates of homelessness amidst formerly incarcerated people, only these estimates likely understate the trouble. Because the effects of intermittent homelessness last longer than your last night on the street, the all-time measures of homeless include those who have experienced homelessness in the last yr. Still, there is not however a mode to calculate this fuller flick of homelessness among formerly incarcerated people.nineteen

Nevertheless, our findings go far clear that the 600,000 people released from prisons each year face a housing crisis in urgent need of solutions. State and local reentry organizations must make housing a priority, and provide boosted services thereafter - a strategy known every bit "Housing First."20 If formerly incarcerated people are legally and financially excluded from safe, stable, and affordable housing, they cannot be expected to successfully reintegrate into their communities.

Recommendations

Excluding formerly incarcerated people from stable housing harms not but individuals, simply public safe and the economy at large. Land- and city-level policymakers have the power to solve this housing crisis:

- States should create articulate-cut systems to aid recently-released individuals notice homes. Even in states like New York, there is often "no central, coordinating force" fix up to ensure that people leaving prison house will land somewhere other than a shelter. Improved systems should assistance incarcerated people understand their housing options before release; find pathways to both short-term and permanent housing; and receive financial supports, such every bit housing vouchers, from the land.

- Ban the box on housing applications. Cities and states should ensure that public housing government and landlords evaluate housing applicants as individuals, rather than explicitly excluding people with criminal records in housing advertisements or applications. A criminal record is not a practiced proxy for ane's suitability equally a tenant.

- End the criminalization of homelessness. Cities should finish the aggressive enforcement of quality-of-life ordinances. Arresting, fining, and jailing homeless people for acts related to their survival is not only cruel; it also funnels formerly incarcerated people back through the "revolving door" of homelessness and penalty, which reduces their chances of successful reentry at great toll to public prophylactic.

- Expand social services for the homeless, focusing on "Housing Outset." States like Utah take made permanent housing for the chronically homeless a budget priority. This successful approach acknowledges that stable homes are often necessary before people can address unemployment, illness, substance use disorder, and other problems. "Housing First" reforms, along with expanded social services, would help to disrupt the revolving door of release and reincarceration.

Appendix

To the extent possible, this study uses terms commonly found in the literature on homelessness in the United states. Nonetheless, given the limitations of the data set we used, the terms and definitions used in this report are not ever consistent with those used by the U.S. Section of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which is the data source we use for comparisons with the general public. Appendix Tabular array 1, below, summarizes the differences between the terms used in this report and terms used past HUD.

| Term | Definitions used in this written report | Equivalent Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Homelessness | Includes people who reported their current, usual residence as:

| "Literally homeless" includes any "Individual or family unit who lacks a stock-still, regular and acceptable nighttime residence, meaning:

|

| Sheltered Homelessness | Includes people who reported that they currently live in a shelter most of the time. The blazon of shelter was not specified. | Includes individuals and families "who are staying in emergency shelters, transitional housing programs, or rubber havens." |

| Unsheltered Homelessness | Includes people who reported that they are currently homeless or have no fixed residence about of the time. | Includes people "whose primary nighttime location is a public or individual place not designated for, or ordinarily used as, a regular sleeping accommodation for people (for instance, the streets, vehicles, or parks.)" |

| Marginal housing | Includes people who reported currently living in a rooming business firm, hotel, or motel most of the time. Different the HUD definition, this is not sectional to those whose housing is being paid for by charitable organizations or government programs. | HUD does non use this term, but includes people living in hotels and motels paid for past charitable or government programs in its definition of "literally homeless." |

| Housing Insecurity | A combined measure that includes people experiencing sheltered and unsheltered homelessness, and people living in marginal housing. | HUD does not use this measure, but includes children living in a hotel or motel due to lack of culling adequate accommodations in its description of "Additional Forms of Homelessness and Housing Instability," using data from the U.South. Section of Education. Other living situations included in HUD's analysis of boosted forms of homelessness and housing instability include:

|

| Source | National Former Prisoner Survey (2008) | U.South. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Resource:

|

Appendix Table ii, beneath, summarizes all of our findings on housing from the National Sometime Prisoners Survey. Note that the "general public" rates come up from our calculation of HUD homeless counts and Census Bureau population estimates for 2008, and that all data is reported equally rates per x,000 population.

| Sheltered Homeless (per 10,000) | Unsheltered Homeless (per ten,000) | Sheltered & Unsheltered Homeless (per 10,000) | Living in rooming firm, hotel, or cabin (per 10,000) | Full housing insecure (per 10,000) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General public | All general public | 13 | viii | 21 | northward/a | n/a | |

| Formerly incarcerated | All formerly incarcerated | 98 | 105 | 203 | 367 | 570 | |

| Race or ethnicity | Blackness | 117 | 123 | 240 | 358 | 598 | |

| Hispanic | 101 | ninety | 191 | 396 | 587 | ||

| White | 66 | 82 | 148 | 350 | 498 | ||

| Gender | Men | 90 | 105 | 195 | 386 | 581 | |

| Women | 156 | 108 | 264 | 226 | 490 | ||

| Race and gender | Blackness men | 108 | 124 | 233 | 369 | 602 | |

| Hispanic men | 103 | 82 | 185 | 409 | 594 | ||

| White men | 56 | 81 | 137 | 383 | 520 | ||

| Black women | 203 | n/a | n/a | 247 | north/a | ||

| Hispanic women | northward/a | n/a | northward/a | 297 | due north/a | ||

| White women | 127 | 87 | 214 | 158 | 371 | ||

| Age | 24 and under | 52 | 91 | 143 | 132 | 274 | |

| 25-34 | 76 | 80 | 156 | 250 | 406 | ||

| 35-44 | 113 | 111 | 224 | 327 | 551 | ||

| 45 or older | 124 | 134 | 258 | 607 | 865 | ||

| Time in prison | Less than 12 months | 127 | 151 | 278 | 368 | 646 | |

| 12-23 months | 103 | 143 | 246 | 330 | 577 | ||

| 24-35 months | 101 | 89 | 190 | 404 | 594 | ||

| 36-59 months | 98 | 87 | 185 | 291 | 476 | ||

| sixty-119 months | 64 | 51 | 115 | 438 | 554 | ||

| 120 months or longer | 69 | n/a | due north/a | 409 | n/a | ||

| Yr released (Years since release) | 2007-2008 (less than 2 years) | 127 | 115 | 242 | 437 | 679 | |

| 2005-2006 (ii-three years) | 64 | 115 | 179 | 292 | 471 | ||

| 2004 or before (4 or more than years) | 37 | 48 | 85 | 185 | 270 | ||

| Prior history | Incarcerated more than once | 136 | 143 | 279 | 434 | 713 | |

| Incarcerated only in one case | 67 | 74 | 141 | 312 | 453 | ||

Figure 4, beneath, explains our method of calculating "housing insecurity." Housing insecurity captures the full extent to which formerly incarcerated people lack stable housing, even if they are not literally homeless. Nosotros define this term in more detail below:

Figure 4. Our metric of housing insecurity includes people living in rooming houses, hotels, and motels, as well as those experiencing homelessness. Using this measure, it's articulate that many more formerly incarcerated people are in precarious housing situations than the charge per unit of homelessness alone suggests.

Figure 4. Our metric of housing insecurity includes people living in rooming houses, hotels, and motels, as well as those experiencing homelessness. Using this measure, it's articulate that many more formerly incarcerated people are in precarious housing situations than the charge per unit of homelessness alone suggests.

Methodology

This study's analyses of homelessness and housing insecurity are primarily based on our analysis of an underutilized government survey, the National One-time Prisoner Survey, conducted in 2008. The survey was a product of the Prison house Rape Emptying Act, and mainly asks well-nigh sexual attack and rape behind bars, simply it also contains some very useful information on housing.

Considering this survey contains such sensitive and personal information, the raw information was not bachelor publicly online. Instead, information technology is kept in a secure data enclave in the basement of the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. Access to the data required the approval of an independent Institutional Review Board, the approval of the Bureau of Justice Statistics, and required us to admission the data under shut supervision.

The practicalities of having to travel across the land in order to query a computer database limited the amount of time that we could spend with the data, and other rules restricted how much data nosotros could bring with us. Additionally, if the number of respondents falling inside whatever 1 group was as well small, we were not allowed to export the data for that group due to privacy concerns.

Using this survey data, we were able to produce the first national estimates of homelessness among formerly incarcerated Americans. We also uncovered many other questions, which nosotros do non yet accept the necessary information to answer on a national level, but which suggest avenues for further research:

- How often do formerly incarcerated people move?

- How often are formerly incarcerated people forced to alive with someone they know considering of a lack of housing options?

- Are formerly incarcerated people probable to reside in overcrowded living spaces?

- How oftentimes are formerly incarcerated people denied housing, compared to the general public?

- How often are formerly incarcerated people in danger of eviction due to the inability to pay hire?

Yet, we believe that the analyses presented in this report brainstorm to illuminate the severe housing-related inequalities experienced past criminalized people.

Data Sources

We used the National Erstwhile Prisoner Survey (NFPS) as our main data source for measuring homelessness and housing insecurity among formerly incarcerated people. This survey began in January 2008 and ended in Oct 2008, and was derived from the Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003, which mandated that the Bureau of Justice Statistics investigate sexual victimization among formerly incarcerated people.

The NFPS dataset includes 17,738 adult respondents who were previously incarcerated in state prisons and under parole supervision at the time of the survey. Individual respondents were randomly selected from a random sample of over 250 parole offices beyond the United States.

It is important to note that because this survey was given to people on parole, it is not a perfect tool to measure homelessness and housing insecurity amongst all formerly incarcerated people. Some incarcerated people are released without supervision, and their ability to attain stable housing may be different than those on parole. Previous inquiry suggests, however, that parole officers accept a minimal (or at best, inconsistent) outcome on post-release housing stability. A national survey of state parole agencies in 2006 institute that near - threescore% - had no housing assistance program. Two regional studies of post-release shelter use, meanwhile, had conflicting findings: In New York, parole increased the likelihood of shelter utilise, only it appeared to reduce shelter use in Philadelphia.21 These mixed results are unsurprising: A synthesis of the literature explains that there is "little collaboration among [corrections and social service] systems and picayune consistency over time. What results is a prisoner reentry system that is disconnected from the housing and homeless assistance services system and from the neighborhoods where released prisoners live." Future research should more than closely examine the upshot of supervision on homelessness and housing stability.

We drew upon specific NFPS survey questions for this report:

- A2. Are you of Hispanic or Latino origin?

- A3. Which of these categories describes your race?

- C1. Are y'all male, female, or transgendered?22

- F15. Where do you currently live near of the fourth dimension?

- B2a, B2b. Date of access.

- B3a, B3b. Appointment of release.

- B13a. Earlier your confinement in [AdmDate2] had you ever served fourth dimension in a land or federal prison? [IF AdmDate2=blank] Earlier the solitude we simply discussed, had y'all ever served time in a state or federal prison?

To measure homelessness in the general public, we used the Department of Housing and Urban Evolution's Bespeak-in-Time counts of sheltered and unsheltered homeless people, along with Demography Bureau population estimates. This data is from 2008, the most recent year in which comparable data for formerly incarcerated people exists.

There is i small, just notable, difference betwixt HUD'due south Point-in-Fourth dimension counts (which we used to calculate homelessness in the general public) and our NFPS information (which we used to summate homelessness among formerly incarcerated people). HUD's Point-in-Fourth dimension counts relied upon special local groups, called Continuums of Care, to tape and report the total number of sheltered and unsheltered homeless people during the last 10 days in January 2008. The National Quondam Prisoner Survey, conversely, asked subjects nearly their housing status directly.

Come across the methodology

Nearly the Prison house Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader damage of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just guild. The system is known for its visual breakdown of mass incarceration in the U.S., as well as its data-rich analyses of how states vary in their utilize of punishment. The Prison Policy Initiative'southward research is designed to reshape debates effectually mass incarceration by offering the "big flick" view of critical policy bug, such every bit probation and parole, women'due south incarceration, and youth solitude.

The Prison house Policy Initiative besides works to shed light on the economic hardships faced by justice-involved people and their families, often exacerbated by correctional policies and practice. Past reports have shown that people in prison and people held pretrial in jail kickoff out with lower incomes even before abort, earn very low wages working in prison house, and face unparalleled obstacles to finding work after they get out.

About the author

Lucius Couloute is a Policy Analyst with the Prison Policy Initiative and a PhD candidate in Sociology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, his dissertation examines both the structural and cultural dynamics of reentry systems. Most recently he co-authored Out of Prison & Out of Piece of work, which provided the starting time-ever unemployment rate among formerly incarcerated people.

Acknowledgements

This report benefitted from the expertise and input of many individuals. The author is particularly indebted to Dan Kopf for retrieving this data from the ICPSR Concrete Enclave, Amy Sawyer for her valuable insight into the state of homelessness today, Alma Castro for IRB assistance, Allen Beck for his insight into the NFPS, the ICPSR staff for their data retrieval back up, Elydah Joyce for the illustrations, Maddy Troilo for background inquiry, my Prison Policy Initiative colleagues, and the Connecticut Coalition to Cease Homelessness for their helpful guidance on "Housing First" strategies.

This report was supported by a generous grant from the Public Welfare Foundation and past our individual donors, who requite us the resources and the flexibility to quickly plow our insights into new movement resources.

Source: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/housing.html

0 Response to "Homeless Being Incarcerated Over and Over Again"

Post a Comment